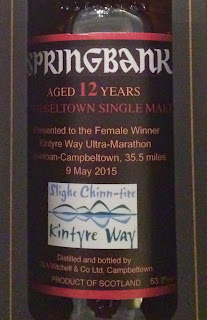

Kintyre Way Ultra Marathon (36 miles)

I am lost to the actualities that surround me, and my whole being expands into the infinite; earth and air, nature and art, all swell up into eternity, and the only sensible impression left is, “that I am nothing!”

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lecture 2, 219

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lecture 2, 219

You hear people say that ultra running changes you. My first ultra was awesome and introduced me to the intense connection with the natural world that comes from running through it for several hours. It stills the mind and settles the soul, but I didn’t feel like I emerged a different person. The second one broke me into tiny pieces and showed me I was braver - or stupider - than I thought.

|

| The relaxed start of the Kintyre Way (to my left Stan Topalian who broke the men's CR, far right William Robertson - the other vegan in the top 4!) |

The Kintyre Way is a tough ultra. I knew that. I had seen the course profile and read a couple of blogs. So bearing this in mind I approached the first 1,000ft climb at a suicidal pace:

|

| QOM on first climb (dark grey section of elevation profile) |

The running along the top through the giant, oddly benevolent, wind turbines was some of the nicest of the race. Then down, then up, then steeply down on tarmac. I continued the suicidal pace tactic. A short road section was followed by a sharp turn and onto a narrow, muddy path flanked by firs. This was followed by the first technical section: a steep rocky climb and then a steep descent (steep featured a lot). Some good running followed, through several little woods including the bewitching Crow Wood. I kept an eye open for druids and mythical creatures but only saw butterflies.

|

| In my own little world Photo: Ken Clark |

A sign pointed runners off the main track into the Deep Dark Wood (it’s actually Sawmill Wood but the trees prefer something more positive, like Deep Dark Wood). There was a sort of path between the trees, a kind of animal track. I had fun hopping over the roots as my eyes fought to focus in the sudden gloom. Some steps quickly deposited me at the first check point. There was some cheering as I stared blankly at the sudden proliferation of bright sunlight and assorted people, then began searching for my drop bag. Elaine Omand quickly stepped into the breach and located it.

At this point I was first woman and about 5th or 6th overall (some relay runners had got ahead and confused me). I had made a note of the check point times for the men’s and women’s course records. I was aiming for somewhere between the two and vaguely surprised (worried) to note I was only a minute outside Peter Buchanan’s record breaking time at this point. I was also beginning to fatigue and had over 20 hilly miles to go…

Running a tough ultra two weeks after my first sub-3 marathon was increasingly looking less than sensible. I had also picked up a cold after London (inevitable). I had then skipped my methotrexate injection the week after London (marathons suppress the immune system and so does methotrexate so it would have meant no chance of shaking off the cold in time), but then taken it the week before the ultra because my joints were starting to stiffen up. I had also spent Wednesday and Thursday on my feet all day at an event. My colleague, Carol, had kindly taken on all the heavy lifting of setting up the University stand because she knew how much the race meant to me. Still though, not ideal preparation.

So by mile 17 I wasn’t super prepared for bouldering…

I was expecting the rocky beach section to be a bit like the coastal path just west of Crail. It wasn’t. I dropped down off one rock and realised the next was now taller than me. I then determined not to drop down. I had to stretch my wee legs to make some of the gaps! This was followed by a couple of boggy bits and then out and up onto the road. As I clambered over the style a man told me I was "the first woman I've seen”. I know Kintyre is remote but that’s one cloistered life. I managed to get some momentum going again as I headed towards the bottom of the third climb. A gate led to a series of hairpin bends leading up. If I hadn’t already been running for two and a half hours this would have been stunning running.

Given how foolishly fast I had started I wasn’t expecting to see any women closing in just yet - later certainly, when I paid for my daft pacing, but not just yet. I looked down at the gate, then looked again. There was a woman coming up fast. Very fast. I wasn’t losing time on the men ahead but she was making time on all of us. I told myself she had to be a relay runner. No one could be making it look so easy at this point. She closed in near the top of the climb and a look at her number confirmed that she wasn’t a relay runner. As she sped by I told myself I would make up the time on the descent. Then I threw up a gel. I was a couple of metres behind as the path fell away. She made even lighter work of the rocky descent than the climb.

My legs had stiffened and were refusing to let me bounce down through the rocks. At the bottom I stumbled into the first of a series of bogs. I think this is the famous cowpat field from Peter’s blog… Not keeping gels down, a bit dehydrated and extremely annoyed to be in second, I wasn’t in the best mood when I arrived into the second and final check point. Rosie tried to persuade me to refill my water bottle. I think I just mumbled at her. Finding a pouch of baby food in my drop bag cheered me up a bit (Ella's 'Mangoes, Mangoes Mangoes' to be precise), but not enough to focus on sensible things like realising I was dehydrated and would need more than the 500ml of water I had stuffed into my pack. There was still a 1000ft climb and 15 miles to go...

I read Mo Farah’s biography when it came out after the Olympics and something struck me then which I have now finally understood. In a race where he came second he wrote: “I lost”.

Rosie tried to tell me I was running really fast but all I could think about was that somebody else was running faster. I wasn’t immediately aware that I was still well within the women’s course record, just that I was losing.

At the next - and last - big climb I took stock. I realised I was overheated (see sunburn) so walked the sunny bits, whilst getting down a gel and some water, then pushed on in the shade. I was slowly catching up with Steven Peters, partly out of a desire for company. I finally caught him and tried to get him to come with me. He did for a bit. Right up to the moment we turned the corner at Lussa Loch.

The clarity and definition under the sun made it look like the Loch was filled with sapphires, topaz and aquamarines.

Then I saw Lucy and so began an hour-long hard run for home. If I had known that it was one of the legends of ultra running, Lucy Colquhoun, I would have given up on the spot. Fortunately for me I didn’t know. I had about a half mile lead over the last 4 miles and by then every step hurt and I wanted more than anything to stop. Only it wasn’t more than anything, or I would have. More than anything I wanted to run my heart out and know by the end, whatever happened, I had nothing more to give. The pain was though almost all-consuming.

But I would suddenly come out of my reverie to see the lambs trotting across the road (they only seem to put fences - and gates - across the Kintyre Way and not round actual fields). I had a brief conversation with a sheep in the road before suddenly hearing a garden full of people cheering. I thought it funny - and quite typical - that I had seen the sheep first (assuming of course that the sheep was real…). Then I saw a woman running around a garden with a pair of the tiniest Scottie dog puppies galloping after her and was instantly smiling.

After that I was too busy thinking about my broken big toe (it’s fine, there was just a pointy stone under it) and the pain in my quads. With about 2 or 3 miles to go I was overcome with an all-encompassing fatigue. I have never in my life felt such fatigue. I wasn’t entirely sure that my legs wouldn’t simply fold under me. I thought the sheep shit strewn verge looked like the most comfortable thing I had ever seen. I hadn’t really done any ultra-specific training, or hills since January, and had run London two weeks before, so this wasn’t surprising.

What was surprising - for me at least - was that my legs didn’t crumple. I could see Campbeltown up ahead and I was soon on the stretch I had walked the day before. I had been looking back over my shoulder every half mile of so, having witnessed how fast Lucy could accelerate, by now it was every 50 metres. Then I was up by the finish tent searching out the dibber. I clocked in and finally did what my legs had been begging me to do for the last 30 minutes. I lay on my back - still wearing my pack - and smiled at the sky.

5 hours 33 minutes (42 minutes inside the previous women's course record).

Whilst the two ultras I have run were very different experiences, in common they have a kind of meditative nirvana. The second also had pain and fatigue but these things fade in the memory as soon as you stop and lie on your back smiling at the sky. You are left only with those long stretches when your body moved with the landscape and the landscape moved with you, when you saw a single leaf and a whole tree simultaneously in sharp definition. When a dragonfly or butterfly danced the breeze beside you. When the land met the sea a thousand feet below you and you knew you were part of it. When you saw a bird dart across the blue and knew exactly how it felt to fly.

This is ultra. It is this sense of not being an integral part of the universe, but being a welcome part. It is not insignificance in the face of the awesomeness of nature: it doesn’t matter that you only have a few atoms to offer on the grand scale of things. You are a part of it and that is all, it is enough.

It is like the Romantic notion of ‘the sublime’, the realisation “that I am nothing” but with the simultaneous gift of knowing: I am part of everything. It is okay. It is perfect. It is enough.

Comments